I presume you have already but still want to doublecheck, have you tried on an alternate browser? Another thing you could try is to clear your cache. Does it also not work on your phone? If it doesn’t work on your phone then i would be inclined to think the problem might be your network? I dunno, maybe someone more savvy could pinpoint the issue better than me.

Immer einer behender als du – Du kriechst – Er geht – Du gehst – Er läuft – Du läufst - Er fliegt: Einer immer noch behender.

Einer immer begabter als du – Du liest – Er lernt – Du lernst – Er forscht – Du forschst – Er findet: Einer immer noch begabter.

Immer einer berühmter als du – Du stehst in der Zeitung – Er steht im Lexikon – Du stehst im Lexikon – Er steht in den Annalen – Du stehst in den Annalen – Er steht auf dem Sockel: Einer immer noch berühmter…

Immer einer beliebter als du – Du wirst gelobt – er wird geliebt – Du wirst geehrt – Er wird verehrt – Dir liegt man zu Füßen – Ihn trägt man auf Händen: Einer immer noch beliebter…

Immer – Immer – Immer.

Robert Gernhardt, Reim und Zeit. Gedichte, Reclam-Verlag, S. 93ff

Finished this last night:

It’s not exclusively or even primarily about nonbinary gender; it covers all sorts of social binaries and what’s wrong with them – in sexuality, relationships, bodies, mental health, conflict, and ways of thinking in general. It also asks us to consider the binary/nonbinary binary…

Almost every social binary comes from some kind of “option A is superior to option B” bias.

Interesting! Added to my list!

Yay! They are doing Monstrous Regiment!!! I love that book! ![]() And Rachel Stott is the artist for Thief of Time… She’s done some Doctor Who and Star Trek!

And Rachel Stott is the artist for Thief of Time… She’s done some Doctor Who and Star Trek!

Recently finished:

https://app.thestorygraph.com/books/54521137-32e0-4889-af21-f71e062fa4f6

YA queer romance with a nonbinary protagonist who is kicked out by his parents, but aside from dealing with that trauma it’s mostly warm-hearted and sweet. (And also the love interest is really super obviously queer but somehow everyone including himself is somehow clueless about it.)

Well, here’s someone I won’t be reading! ![]()

This morning I was looking around to read what people have said about Zweig and there, from 2010, was this blazing attack by the translator Michael Hoffman. You’ve heard the word takedown? You’ve never read a takedown till you read this. It’s so brutal, and from what I got through in The World of Yesterday, fair. But, boy, did it make a lot of people furious. None of the responses lands a single blow; they just all seem to be of the “how dare you say this about Zweig who was driven out by the Nazis” genre.

Here’s an excerpt:

"…this popular-again populariser who, like the Kitschmeister Gustav Klimt, is glitteringly and preposterously back in fashion, and neither of them any better than they were the first time round.

Polygrapher Zweig (‘twig’), dubbed ‘Erwerbszweig’ (something like ‘productive branch of the economy’) in catty, envious Vienna: this anxious success and oh-so-modest failure; bestselling and most-translated German-language author before World War Two, and now again book of the week here, rediscovery of the century there, and indulgently reviewed more or less everywhere; this uniquely dreary and clothy sprog of the electric 1880s; this un-Austrian Austrian and un-Jewish Jew (Joseph Roth – who has certainly spoiled me for Zweig – was both, to the max); not a pacifist much less an activist but a passivist; this professional adorer, schmoozer, inheritor and collector, owner of Beethoven’s desk and Goethe’s pen and Leonardo and Mozart manuscripts and busy Balzac proofs and contemporaries out the wazoo, plus 4000 manuscript collection catalogues, who logged his phone calls and logged his letters and logged his books, and, who knows, probably logged his logs; this cosmopolitan loner and blue-riband refugee, so ‘hysterically discreet’ that he got married by proxy; who, in the words of the writer Robert Neumann, ‘spent his life on the run. From the Great War to Switzerland. From the symbolic firing-squad across the Channel. From Blitzed London to the safety of provincial Bath. From Hitler’s threatened invasion of England to the USA. From Roosevelt’s impending entry into the war to Brazil. He even fled Rio for a Brazilian mountain resort. From there there was no more running’; who left a suicide note which, like most of what he wrote, is so smooth and mannerly and somehow machined – actually more like an Oscar acceptance speech than a suicide note – that one feels the irritable rise of boredom halfway through it, and the sense that he doesn’t mean it, his heart isn’t in it (not even in his suicide); this person whose books I briefly thought I wouldn’t mind reading, before, while setting down the umpteenth of them amid groans (it was the novella Confusion), adding the stipulation to myself: yes, but only if they’d been written by someone else.

Stefan Zweig just tastes fake. He’s the Pepsi of Austrian writing. He is the one whose books made films – 18 of them, and that’s the books, not the films (which come in at a stupefying 38). It makes sense: these are hypothetical and bloodless and stiltedly extreme monuments and monodramas for ‘teenagers of all ages’, as someone said, books composed for the bourgeoisie to give itself culture or a fright, which needed Hollywood or UFA to make them real, to give them expressions, faces, bodies, rooms and dialogue; and to drain some of the schematic grand guignol out of them. Of course he failed the Karl Kraus test – who didn’t? Kraus quotes some yea-sayer to the effect that Zweig with his novellas had conquered all the languages of the world, and adds two words of his own: ‘except one’. The story went the rounds that Zweig had his manuscripts checked for grammatical errors by a German professor, which gets most things about Zweig: the ineptitude, the anxiety to please, the respect for authority, and the use of others.

It’s not easy to think of a writer so poorly thought of by his maybe peers, and it can’t all be attributed to envy or resentment of his great inherited wealth, easy success, unproblematic seductions and vast readership. Even among writers, there may be odd moments of honesty. Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who for the best part of 30 years shared a publisher with Zweig, Anton Kippenberg, founder of the Insel Verlag, wrote to dispraise him; when Kippenberg, foolishly trying to change Hofmannsthal’s mind, informed him, publisher-paternalistically, that Zweig had won a poetry prize, Hofmannsthal wrote back in a (for him) strange blaze of candour, to say that the prize wasn’t a prize at all, but a bursary, and that Zweig had had to share it with ‘eight other sixth-rate talents’. When Hofmannsthal and Max Reinhardt started the Salzburg Festival in 1919, it was one of their conditions that Zweig – who had recently moved to Salzburg – be rigorously excluded. (Zweig took to absenting himself from Salzburg every summer while the festival was on.) Hofmannsthal’s friend Leopold von Andrian put himself through a Zweig novella (that same Confusion I mentioned earlier) ‘reluctantly, a spoonful a day, like a nasty-tasting medicine’, and, in the course of a comprehensive, paragraph-long taking-apart, wrote: ‘each sentence incredibly pretentious, false and empty – the whole thing a complete void’. In his memoir, The Play of the Eyes, Elias Canetti recalls a meeting with Zweig, who had come back to Vienna for two reasons: to get his teeth seen to, and to set up a new house that would publish his books. The next sentence is: ‘I believe nearly all his teeth were extracted.’ The malicious and inescapable and (in a master like Canetti) perfectly deliberate undercurrent is that of course Zweig’s books are not worth talking about. The exeunt omnes of his teeth is a better and more interesting outcome than anything to do with the publication – or extraction? – of the books.

Even Joseph Roth, a complicated friend of Zweig’s who more or less lived off him for the last ten years of his life, picked holes in the style of each successive book he was sent, partly as a way of discharging his debt, and partly to preserve his independence. The veteran Germanist Hans Mayer remembers a visit to Musil in Switzerland in 1940; Musil couldn’t get into the USA, and Mayer was suggesting the relative obtainability of Colombian visas as a pis aller. Musil, he wrote, ‘looked at me askance and said: Stefan Zweig’s in South America. It wasn’t a bon mot. The great ironist wasn’t a witty conversationalist. He meant it … If Zweig was living in South America somewhere, that took care of the continent for Musil.’ Nor was it just the Austrians, to whom such Schmäh was in their mothers’ milk. Hermann Hesse thought neither Zweig’s poetry nor ‘his many other books’ deserved to outlast the day. When Kippenberg was told that his author had a part interest in a factory, he is said to have quipped: ‘What – another one?’ When Zweig moved to England in 1934 (and was naturalised in 1938), it was taken semi-jocularly in many literary quarters to be a major item in that ongoing ‘punishment of England’ (‘Gott strafe England’) that had been on the German agenda since 1914.

The composer Hanns Eisler records a meeting between Brecht and Zweig in London. Brecht, who ‘of course never read a line of Zweig’ (one admires the economy of effort), sees him only as a possible source of funds for his theatre; Zweig, no doubt, is interested only in adding the notch of another great man to his metaphorical bedpost. Brecht asks Eisler for a tune. Unfortunately, the tune he asks for is ‘Song of the Vivifying Effect of Money’, and it’s not lost on Zweig. Later, in spite of everything, one would think, the two writers go for lunch together, and when Brecht comes back Eisler – really lovely, the stringent cut-to-the-chase of these Marxist types! – asks him how much Zweig shelled out for lunch. ‘Two and six,’ Brecht replies, a Lyons Corner House or something (and at the time the multi-millionaire Zweig was residing in Portland Place), and then it’s straight back to discussion of the revolution.

Further west, in Princeton, or much further, in Pacific Palisades, Thomas Mann and his family spent diverting evenings – this in 1939 – debating which of Zweig, Ludwig, Feuchtwanger and Remarque was the worst writer. Emil Ludwig himself, in an obituary, wrote that none of Zweig’s writings had affected him in a way that could compare with his death. It’s a well-meaning but damning and finally ineluctable summation. I have seen the Brazilian press photograph of Zweig and Lotte, his second wife, lying dead of their overdoses of veronal on two pushed-together single iron bedsteads, he on his back, mouth a little agape, in a sweat-stained shirt and knitted tie, she on his shoulder in a floral wrap and clean hair, and you can practically hear the ceiling fan going round. It makes Weegee look tame."

I recognized the name and looked him up to find out from where. The Grand Budapest Hotel was inspired by his work. Huh.

ETA: An alternate take. Interview: George Prochnik, Author Of 'The Impossible Exile' : NPR

Speaking as an employee of an independent bookstore, I’m happy to say we were still very busy yesterday. Amazon and ebooks have so far not been enough to dissuade passionate readers from buying local and deliberately making an effort to support their favorite bookstores.

@Hanglyman there are no local bookstores near me, I don’t have a car and the public transport near my residence sucks.

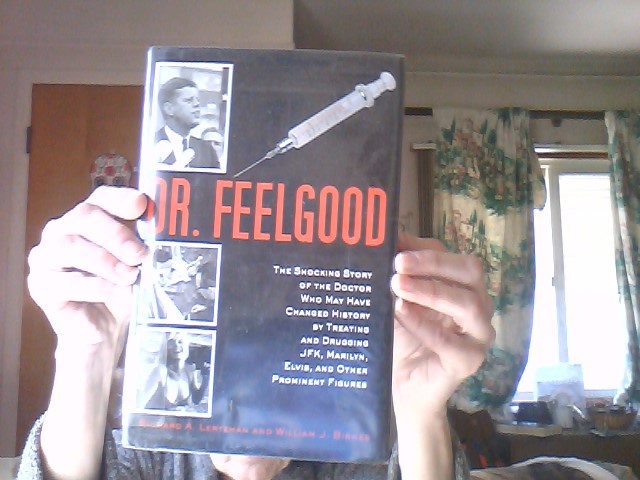

Having assuaged my new-found guilt, lol, here’s what I’m reading, 2d time 'round. I ordered it from Alibris.

I’m all for transparency regarding the health of the POTUS. Reporting the true facts about them makes them human. I dunno about you folks, but this primitive exalting of leaders is getting really, really ancient and I for one am sick of it.