I have yoinked that for a couple of other platforms that I comment on. It does have a Canadian focus, but there’s more than enough general things there that could be useful for non-Canadians.

Oh wow, thanks for that quote.

The AI bros and all execs peddling AI want exactly that: turn all creative and brain work into slave work, by setting it into competition to AI slop.

Btw, may I recommend the most fabulous blog https://pivot-to-ai.com/ ?

TIL, thanks!

That’s a good one. Reminds me of fare like “Web3 is going great”.

As far as Wiener, behind the cut is an extended excerpt from Cybernetics that includes the quoted material, consisting of about the last 4 pages of the original 1947 introduction (~1,100 words). It’s as insightful and as relevant today as the shorter excerpt suggests.

"Let me now come to another point which I believe to merit attention."

Let me now come to another point which I believe to merit attention. It has long been clear to me that the modern ultrarapid computing machine was in principle an ideal central nervous system to an apparatus for automatic control; and that its input and output need not be in the form of numbers or diagrams but might very well be, respectively, the readings of artificial sense organs, such as photoelectric cells or thermometers, and the performance of motors or solenoids. With the aid of strain gauges or similar agencies to read the performance of these motor organs and to report, to “feed back,” to the central control system as an artificial kinesthetic sense, we are already in a position to construct artificial machines of almost any degree of elaborateness of performance. Long before Nagasaki and the public awareness of the atomic bomb, it had occurred to me that we were here in the presence of another social potentiality of unheard-of importance for good and for evil. The automatic factory and the assembly line without human agents are only so far ahead of us as is limited by our willingness to put such a degree of effort into their engineering as was spent, for example, in the development of the technique of radar in the Second World War.

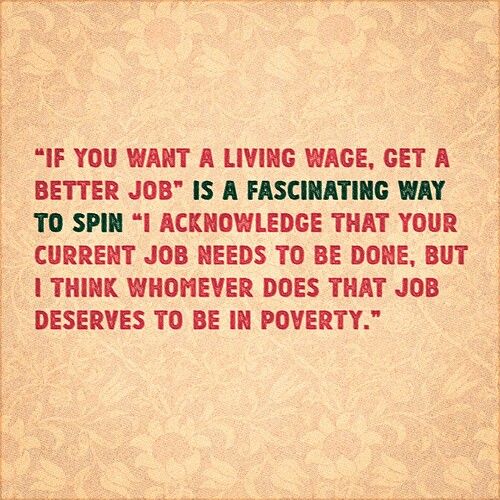

I have said that this new development has unbounded possibilities for good and for evil. For one thing, it makes the metaphorical dominance of the machines, as imagined by Samuel Butler, a most immediate and non-metaphorical problem. It gives the human race a new and most effective collection of mechanical slaves to perform its labor. Such mechanical labor has most of the economic properties of slave labor, although, unlike slave labor, it does not involve the direct demoralizing effects of human cruelty. However, any labor that accepts the conditions of competition with slave labor accepts the conditions of slave labor, and is essentially slave labor. The key word of this statement is competition. It may very well be a good thing for humanity to have the machine remove from it the need of menial and disagreeable tasks, or it may not. I do not know. It cannot be good for these new potentialities to be assessed in the terms of the market, of the money they save; and it is precisely the terms of the open market, the “fifth freedom,” that have become the shibboleth of the sector of American opinion represented by the National Association of Manufacturers and the Saturday Evening Post. I say American opinion, for as an American, I know it best, but the hucksters recognize no national boundary.

Perhaps I may clarify the historical background of the present situation if I say that the first industrial revolution, the revolution of the “dark satanic mills,” was the devaluation of the human arm by the competition of machinery. There is no rate of pay at which a United States pick-and-shovel laborer can live which is low enough to compete with the work of a steam shovel as an excavator. The modern industrial revolution is similarly bound to devalue the human brain, at least in its simpler and more routine decisions. Of course, just as the skilled carpenter, the skilled mechanic, the skilled dressmaker have in some degree survived the first industrial revolution, so the skilled scientist and the skilled administrator may survive the second. However, taking the second revolution as accomplished, the average human being of mediocre attainments or less has nothing to sell that it is worth anyone’s money to buy.

The answer, of course, is to have a society based on human values other than buying or selling. To arrive at this society, we need a good deal of planning and a good deal of struggle, which, if the best comes to the best, may be on the plane of ideas, and otherwise—who knows? I thus felt it my duty to pass on my information and understanding of the position to those who have an active interest in the conditions and the future of labor, that is, to the labor unions. I did manage to make contact with one or two persons high up in the C.I.O., and from them I received a very intelligent and sympathetic hearing. Further than these individuals, neither I nor any of them was able to go. It was their opinion, as it had been my previous observation and information, both in the United States and in England, that the labor unions and the labor movement are in the hands of a highly limited personnel, thoroughly well trained in the specialized problems of shop stewardship and disputes concerning wages and conditions of work, and totally unprepared to enter into the larger political, technical, sociological, and economic questions which concern the very existence of labor. The reasons for this are easy enough to see: the labor union official generally comes from the exacting life of a workman into the exacting life of an administrator without any opportunity for a broader training; and for those who have this training, a union career is not generally inviting; nor, quite naturally, are the unions receptive to such people.

Those of us who have contributed to the new science of cybernetics thus stand in a moral position which is, to say the least, not very comfortable. We have contributed to the initiation of a new science which, as I have said, embraces technical developments with great possibilities for good and for evil. We can only hand it over into the world that exists about us, and this is the world of Belsen and Hiroshima. We do not even have the choice of suppressing these new technical developments. They belong to the age, and the most any of us can do by suppression is to put the development of the subject into the hands of the most irresponsible and most venal of our engineers. The best we can do is to see that a large public understands the trend and the bearing of the present work, and to confine our personal efforts to those fields, such as physiology and psychology, most remote from war and exploitation. As we have seen, there are those who hope that the good of a better understanding of man and society which is offered by this new field of work may anticipate and outweigh the incidental contribution we are making to the concentration of power (which is always concentrated, by its very conditions of existence, in the hands of the most unscrupulous). I write in 1947, and I am compelled to say that it is a very slight hope.

Oh yes, indeed. Thanks for sharing!

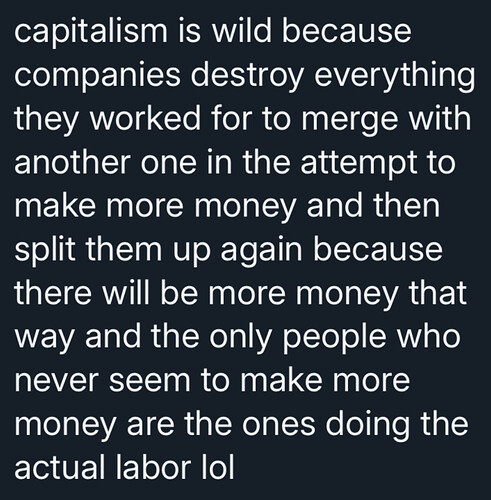

I’ve witnessed this from the inside. I’ve never worked for PE, which is the most extreme example, but I’ve seen first hand when a company that is growing (often due to treating and paying their employees well) gets acquired by a bigger company, immediately lays people off (so now the ones who are left are doing 2x or more of the work for the same pay), acquires other companies that are failing, puts the failing companies under the successful one, then demand the successful one continue to grow at pace with fewer employees doing more work, including somehow turning around product lines that were never going to succeed.

Then they act surprised when the successful acquisition division underperforms.

There’s also the really weird dynamic that they often get rid of the management from the successful acquisition and put the management from the failing acquisition in charge. It makes no business sense, but I think it’s largely to do with the management from the successful acquisition objecting to layoffs and mistreatment of employees, while the unsuccessful management is fully on board with it (there was a reason they were unsuccessful).

OK, sorry for too much information there. Just observing that, in my 30 year career, the companies that have been most successful are the ones that act most like they are employee-owned. Inevitably, when those successful companies either 1. Get swallowed up by a megacorp that implements its own employee-toxic policies or, 2. Decide they need to get more “corporate” and bring in management from less-successful megacorps, success dries up and they wonder why…

My roommate works for an insurance company that focuses on businesses, and it. Is. a. shitshow. They are constantly firing entire divisions, increasing the workload of existing employees, and they keep giving excuses that they are unable to give people raises because the money just isnt there. The irony is that during company-wide meetings they’ll boast about how profits are way way up and how things are looking great for investors. Needless to say my roommate has been looking for work elsewhere since…. last year? Job market here has been tough because my partner has also had a hard time getting interviews and she’s been looking for better employment for a while too.

I watched the transition I outlined above in a private, single-owner company. The founder treated employees very well, encouraged innovation, put almost all of the profits back into the company in terms of bonuses, hiring more people, or investing in new facilities/equipment/capabilities. Then the founder died and his son took over. They stopped hiring workers, hired a bunch of management from megacorp competitors who came in and made things shitty while slowing growth, and almost completely stopped bonuses and raises. The inflection point was incredibly obvious to anyone with eyes. The year those changes were made was the last year with double-digit growth. After that, the company pegged to the overall industry growth rate of mid-single-digits.

That was all without the influence of Private Equity. With PE, take all of the above and dial it to 11.

I recall from many years ago reading about an actor making a comment about how geek/nerd culture infantilizes men and the internet blowback they had gotten. Occasionally it’ll pop into my mind and today i actually looked it up, it was Simon Pegg and honestly? I totally agree with him.

Pegg touches on the growing consumerism attached to genre films that has preyed on audiences’ nostalgia for youth. Citing the philosophies of cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard, Pegg explains how society has become infantilized to distract us from the real horrors of the world

A major aspect of nerd culture is the monetization of nostalgia. There’s other aspects around this that I think about, things like nerdy folks are playful and inquisitive. Very child-like things that are good to be in touch with but this key aspect of nerd culture is inherently commoditized and leveraged, so I feel like Pegg’s opinion hits things on the head that we should be careful of how we associate ourselves with our geekdom, and pun intended, how we buy into it.

I dunno, this has been on my mind on and off for a long time and is one of the reasons why I’ve really put the breaks on my consumerism. It’s helped me be more judicious on what I spend my time and money on.

“Merch” Yeah, I dedicate my merch spend, what little it is, on small productions.

I’ve been fucked by the system. Does that count?