I guess they tried to enter the market but didnt have any luck.

Grew up in Florida and “next Friday” means the Friday next week. “This coming Friday” or “this Friday” specifies the one this week.

Same for the other side of the continent.

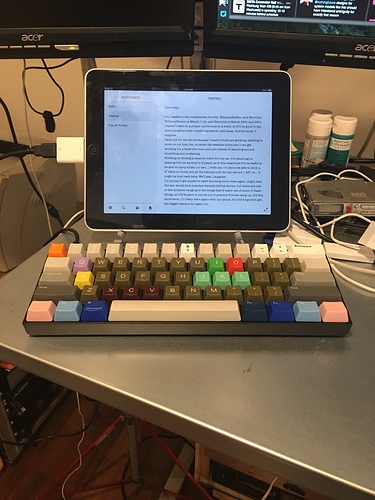

My current whips:

First is a hand built 40% and wired Alps switches run through a teensy 2.0 and custom firmware.

Second one is a 60% with cherry mix clear switches, custom key caps, and the caps lock remapped to a function key to give me arrows.

I’ve got a decent rubber dome around, too- it it’s a bit fickle sometimes.

It know it’s common usage for “next friday” to mean “not next friday, but some other friday, maybe a week later, or multiple fridays, starting a week afer next friday,” but it is utter nonsense, and got me in a lot of trouble in school growing up, because I was ready for the trip next friday, but not the following friday, or the next-following friday, which were what they meant.

Maybe it was wednesdays, I can’t remember, but it wasn’t next whicheverdays.

I haven’t known people who were that careless about their specification. I grew up using “this Friday” to mean “this coming Friday,” and “next Friday” to mean the Friday that ends the week we haven’t yet started. I know lots of people that think “next Friday” is a week sooner than I’m expecting it, but I don’t know anyone who’s expecting it later than I am.

I was briefly confused by “quarter of” because most SoCal natives don’t use it, but we have enough Midwestern immigrants here that they clued me in.

I still need some Victorian Brit to explain to me when “Wednesday week” is supposed to be.

I wonder if this whole thing actually arises from the tendency in many languages for a time descriptor to get dropped.

We say “half past six”, Germans say “halb sieben”, Russians “poluvina sedmovo” but the French “six heures et demie”.

At the same time there are expressions where interval descriptors get dropped, like “Wednesday [next] week” —> Wednesday week.

I suspect forms like “next Thursday” have dropped the “week” somewhere in there.

@MarjaE, if you’re going to disagree with someone’s post it would be nice if you could reference the someone so they could respond.

I’d be interested to read your source on that because there is no dative case in English, it’s entirely represented by helper words. The only really distinct cases in English are nominative and genitive with some pronouns that represent the other cases, e.g. I, me, mine, she, her, hers. The dative is normally represented by “to” or “from”, not “of”.

There are different constructions for time in English and the modern one uses a dative after the half hour (twenty to three) and the word “past” for after the hour. But there is an older construction, now I think fully obsolete, of which I was thinking.

In an expression like “it was about the fifteenth minute of the third hour and the clock struck the quarter”, suggesting that the “of” is dative can surely only arise from confusing Latin and English (a vice to which many schoolmasters were prone)? The natural assumption is that it was the fifteenth minute belonging to the third hour. And when we see that in another Indo-European language the hour is explicitly and without possibility of confusion in the genitive (tretovo), we have to consider the possibility that it’s apparent genitive construction in English is just that.

But even the example you give is arguable. I mentioned in my original post that according to some linguists time and number may originally have had their own special case, which has merged with other cases. You’re saying that in Vulgate Latin (which I kind of read but am not expert) time is in the ablative case. The ablative in Latin is a catchall case for some of the old lost Indo-European cases, which makes perfect sense. But in Russian the lost cases have been swept into the genitive, dative and prepositional. Other languages like German have different allocations again; German uses nach and vor, which I agree are dative.

I would also take strong issue with the word “hack”. Languages are not hacked; people adopt a usage for a variety of reasons, sometimes it sticks and sometimes it doesn’t. Linguistics is descriptive, only in the fantasy world of classical schoolmasters does someone sit down and think “how do I put this bit of Latin syntax into English and then get everybody to use it.”

(Years ago when briefly teaching basic physics I gave a top set some bits of Newton’s Principia to translate, relevant to the course. I thought I was doing a bit of uniting C P Snow’s two cultures. Instead, I was complained at by the classics department who said it was hard enough to get the kids to learn Latin anyway without being exposed to Newton’s barbarous syntax.)

Latin has a distinct genitive case.

Vulgar Latin usually uses de+(noun) instead of the genitive, taking on the roles of the genitive. I think it’s de+ablative but could be wrong. French follows the same pattern.

English has a distinct genitive, usually marked with 's.

English sometimes uses of+(noun) instead of the genitive, taking on most of the same roles as the genitive. If the Latin was de+ablative, then an early English borrowing would naturally be of+dative since English has never had an ablative.

I find it helpful to think of English as having the old Nominative, Accusative, Genitive, and Dative, like other Germanic languages. Given the merged forms, I can understand why some people find it useful to reduce it to 2 or 3 cases.

But why?

English isn’t a Romance language. It’s a hybrid of western Germanic dialects with its roots, presumably, in Gothic. The Romanised languages were pushed out by the Germanic invaders. As Germanic languages, and with later Scandinavian input, they had only the four cases we now find in German. By Old English, though there were notionally the four cases, the modern English pattern of three only (nominative, objective, genitive) was already visible in the pronouns.

Did you have a classical education by any chance? I didn’t; I had nothing to do with Latin or Greek till I had to learn them a bit at university, where I also did basic linguistics.

I’m defending the thesis here that complex case endings are old tech, and I’m a little nostalgic for languages that had strong inflections and loose word order.

Because Proto-Germanic had already lost the ablative, English never had it. So phrases which take the ablative in Romance languages tend to take the dative in Germanic ones.

Cough. Good old days of technology.

Even though it is merely a GIF, I can still hear him.

And smell him too.

Ballmer was irritating on several levels, lacking in dignity and over the top. But oh how preferable he seems to the new Randians - Zuckerberg, Musk - with their robotic far-right dial in views and pretensions to being more than successful, if somewhat sociopathic, businessmen. I think if I met Ballmer I’d buy him a beer.

You’re too generous. I wouldn’t go that far. I think I would politely abstain from kneeing him in the groin.

How Facebook:

What could possibly go wrong?

You’d think hope pray that Zuckerberg would realise that the wisdom of crowds has been comprehensively disproven, especially when it comes to the treatment of minorities.

Remember when information technology was about creating, editing, storing, retrieving and presenting data, not trying to bring about dystopia one ill considered cost saving reaction at a time?

American midwest dialect is definitely influenced by German and other non-Anglophone European immigrants.