[excerpt from The Diaries of Other Pendragon © 2017 by TrilloCom LLC]

I have always felt that I am better suited to a life of natural philosophy than the soldier’s career. As a chirurgeon and aspiring physician I have acquired much knowledge of anatomy, and when I had the chance I have studied subjects ranging from astrology to alchemy.

When I heard whispers in the universities of the work of the Pole Copernicus, who was about to publish a work of radical astronomical theory, my first thought was concern that the Pope, fearful of his position in the struggle against the heretic Luther, might attempt to suppress the work.

Worse, Mr. Collins, that learning-sponge, had announced that he intended to travel to Nuremberg to acquire a copy of Copernicus’ book, and I feared for the free dissemination of knowledge if he got his hands on the master’s intellectual property.

An adventurer’s instincts cannot be easily erased. My motto has always been, “Say Yes to the Quest!”. I saddled my destrier and set off on the road to Nuremberg to meet Copernicus and offer my protection.

Nuremberg, in the heart of Brass Valley, attracted natural philosophers and artificers of all sorts. There was fanciful talk of clocks so small that people could wear one about their necks, but no one questioned the sort of society that would result when everyone walked about obsessed with the time, ignoring polite discourse with their neighbours. Some proposed that a cunningly-contrived pair of lenses would allow anyone to see things too far away for the eye, but no one considered the grave threat to privacy that this would pose. All in all, I found the city disappointingly lacking in professors of ethics.

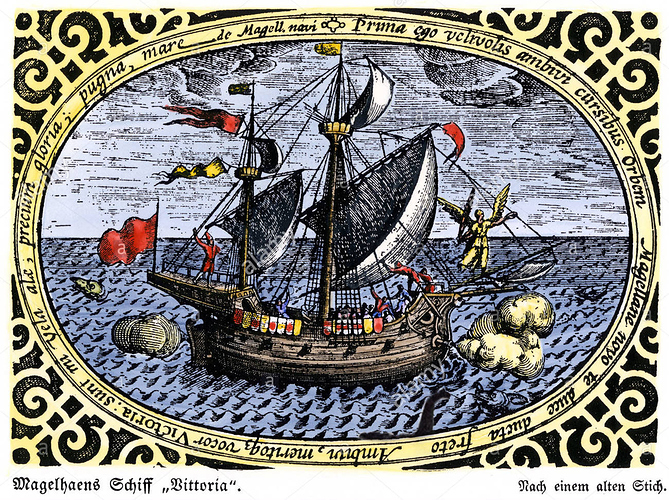

I sent my respects to Master Copernicus and proposed that we meet the following day. At dawn, however, I awoke to voices in the street and a familiar harpstring sensation, and looked out of the window to see Mr. Collins, in a choleric mood most unlike him, loudly addressing a strange being wearing a plain brown wrapper. She (for it was a she) threw off her garment, revealing herself to be a member of that family of large deer, known as moose, that I had seen when I travelled with Prince Madoc to the New World.

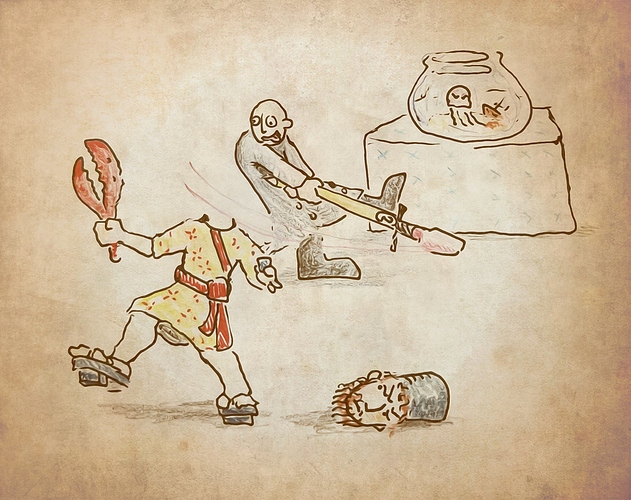

Her gesture seemed to enrage Mr. Collins even more, but he got control of himself and said coldly, “Hello. My name is Mr. Collins, Librarian. You bit my sister. Prepare to die.” Raising a hefty-looking scroll above his head, he assumed a stance in the “drunken pedant” fighting style that he must have picked up in Beijing.

Refusing to be cowed, the moose pawed the ground and snorted. “I am Maple, Daughter of Pudf, Moosekin of the Clan Clamphoof. Your sister deserved it!” Drawing an ornate sword, she charged.

Lady Maple struck a ferocious blow that cut deeply, but Mr. Collins got the measure of her sword and skillfully deflected her next thrusts with deft little movements of his scroll, all the while criticizing her grip and suggesting that she work on her follow-through. The constant belittling was starting to have its effect when Mr. Collins switched to a more aggressive style and began to taunt her, describing how he was going to hang her head above his fireplace, which I personally think was tacky, but it had its effect, and after a few more minutes of his goading I heard a sickening thud and realized that it was over. Yes, he had talked her head off.

I got my autographed copy of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and left Nuremberg forever.